2. Significance of the Site

Figure 2.1 Durham Cathedral (Ollie Wilkins)

Figure 2.2 St. Cuthbert’s Tomb, Durham Cathedral

Figure 2.3 Norman Chapel, Durham Castle

2.1. Original Justification for the Inscription of the Site on the World Heritage List (1985)

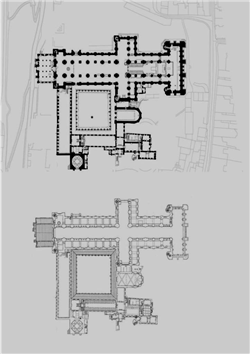

Durham Cathedral is the finest example of Early Norman Architecture in England. However, although Romanesque in origin, the introduction of rib vaults, the use of the structural pointed arch and of lateral abutments (in effect, diminutive flying buttresses albeit concealed within the roofs of the galleries) all dating to the years 1137-1139, represent the first stage in developments which revolutionised the architecture of Europe. 1

St. Cuthbert, who is buried in the Cathedral, was a key figure in the conversion of Europe to Christianity and played much the same role in the north of the country that St Augustine played in the south. His relics include some of the oldest surviving embroidery in Europe. The Cathedral also contains the tomb of the Venerable Bede (673-735 AD), another influential figure, whose historical writings are crucial to the importance of Dark Age Britain.

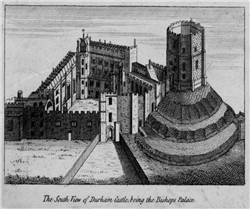

In architectural terms, the castle is less important, but visually, it dramatically illustrates the concept of the motte and bailey castle; it includes features of notable architectural interest such as the Norman Chapel (the oldest building in Durham), the Norman Gallery, and the richly decorated entrance to the original Great Hall, and it demonstrates in structural terms the change of function from castle to palace to university. However, it is in relationship to the Cathedral that its justification lies, since, towering over the town in truly awesome fashion, they symbolise together the spiritual and secular powers of the Bishops Palatine in a manner which, once seen, will never be forgotten.

2.2 Durham World Heritage Site’s Statement of Outstanding Universal Value (SOUV)

An updated Statement of Outstanding Universal Value was produced in December 2010, put forward for public consultation, approved by ICOMOS UK, and ratified by UNESCO in June 2013.

2.2.1 What is the Statement of Outstanding Universal Value?

The Statement of Outstanding Universal Value identifies what the key attributes of the site are. Without these attributes, its value as a World Heritage Site would be compromised.

The current statement is based on the original documentation for the inscription of the site in 1986, as well as later developments that reflect the evolution of UNESCO’s attitudes towards the preservation of heritage.

The fact that the statement of Outstanding Universal Value is based on the 1986 documentation that led to Durham’s inscription on the World Heritage List means that there were certain constraints with regards the content of the statement. The statement relates to the Outstanding Value of the site, as identified by the World Heritage Committee in 1986.

2.2.2 Relevance of the Statement of Outstanding Universal Value

It is essential that all parties involved with the World Heritage Site in any way do their utmost to ensure the preservation of these attributes. The following statement therefore serves as a reference document.

Figure 2.4: View of the Cathedral from Palace Green, 18th century (Durham University Library)

2.2.3 Durham’s Statement of Outstanding Universal Value (As ratified by UNESCO in June 2013).

Brief Synthesis

Durham Cathedral was built between the late 11th and early 12th century to house the bodies of St. Cuthbert (634-687 AD) (the evangeliser of Northumbria) and the Venerable Bede (672/3-735 AD). It attests to the importance of the early Benedictine monastic community and is the largest and finest example of Norman architecture in England. The innovative audacity of its vaulting foreshadowed Gothic architecture.

The Cathedral lies within the precinct of Durham Castle, first constructed in the late eleventh century under the orders of William the Conqueror.

Figure 2.5: The South View of Durham Castle, being the Bishop’s Palace. After S and N Buck, 1728

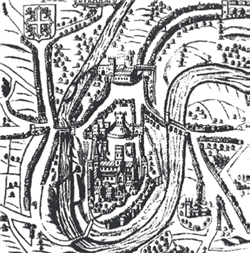

Figure 2.6: Map of Durham by John Speed, c.1611

The Castle was the stronghold and residence of the Prince-Bishops of Durham, who were given virtual autonomy in return for protecting the northern boundaries of England, and thus held both religious and secular power.

Within the Castle precinct are later buildings of the Durham Palatinate, reflecting the Prince-Bishops’ civic responsibilities and privileges. These include the Bishop’s Court (now a library), almshouses, and schools. Palace Green, a large open space connecting the various buildings of the site once provided the Prince Bishops with a venue for processions and gatherings befitting their status, and is now still a forum for public events.

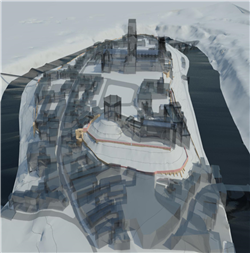

The Cathedral and Castle are located on a peninsula formed by a bend in the River Wear with steep river banks constituting a natural line of defence.

These were essential both for the community of St. Cuthbert, who came to Durham in the tenth century in search of a safe base (having suffered periodic Viking raids over the course of several centuries), and for the Prince-Bishops of Durham, protectors of the turbulent English frontier.

Figure 2.7 Aerial view of the Durham Peninsula

Figure 2.8 Durham Gospels

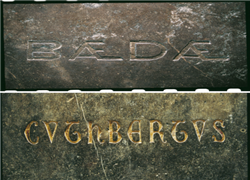

Figure 2.9 Inscriptions in Durham Cathedral

The site is significant because of the exceptional architecture demonstrating architectural innovation and the visual drama of the Cathedral and Castle on the peninsula, and for the associations with notions of romantic beauty in tangible form. The physical expression of the spiritual and secular powers of the medieval Bishops’ Palatinate is shown by the defended complex and by the importance of its archaeological remains, which are directly related to its history and continuity of use over the past 1000 years. The relics and material culture of three saints, (Cuthbert, Bede, and Oswald) buried at the site and, in particular, the cultural and religious traditions and historical memories associated with the relics of St Cuthbert and the Venerable Bede, demonstrate the continuity of use and ownership over the past millennium as a place of religious worship, learning, and residence in tangible form. The property demonstrates its role as a political statement of Norman power imposed on a subjugate nation and as one of the country's most powerful symbols of the Norman Conquest of Britain.

Criteria

There are ten criteria by which sites are assessed to determine whether they are worthy of inscription on the World Heritage List. Sites must meet at least one of these to be eligible. According to the World Heritage Committee, Durham meets the following three criteria:

Criterion (ii): “to exhibit an important interchange of human values, over a span of time or within a cultural area of the world, on developments in architecture or technology, monumental arts, town-planning or landscape design,”

Durham Cathedral is the largest and most perfect monument of ‘Norman’ style architecture in England. The small astral (castle) chapel for its part marks a turning point in the evolution of 11th century Romanesque sculpture

Figure 2.10: Durham Cathedral from the East End

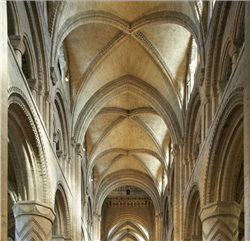

Figure 2.11: Nave Vaulting, Durham Cathedral

Figure 2.12: High Altar, Durham Cathedral

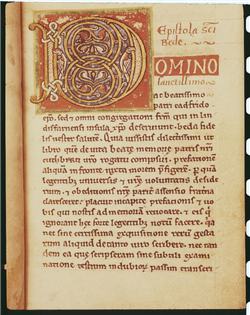

Figure 2.13: Page from Bede’s Manuscript

Criterion (iv): “to be an outstanding example of a type of building, architectural or technological ensemble or landscape which illustrates (a) significant stage(s) in human history”

Though some wrongly considered Durham Cathedral to be the first ‘Gothic’ monument (the relationship between it and the churches built in the Île-de-France region in the 12th century is not obvious), this building, owing to the innovative audacity of its vaulting, constitutes, as do Spire [Speyer] and Cluny, a type of experimental model which was far ahead of its time.

Criterion (vi): “to be directly or tangibly associated with events or living traditions, with ideas, or with beliefs, with artistic and literary works of outstanding universal significance. (The Committee considers that this criterion should preferably be used in conjunction with other criteria)”

Around the relics of Cuthbert and Bede, Durham crystallized the memory of the evangelising of Northumbria and of primitive Benedictine monastic life.

Integrity

The physical integrity of the property is well preserved. However, despite a minor modification of the property’s boundaries in 2008 to unite the Castle and Cathedral sites, the current boundary still does not fully encompass all the attributes and features that convey the property’s Outstanding Universal Value. The steep banks of the River Wear, an important component of the property’s defensive role, and the full extent of the Castle precinct still lie outside the property boundary.

There are no immediate threats to the property or its attributes. The visual integrity of the property relates to its prominent position high above a bend in the River Wear, and there is a need to protect key views to and from the Castle, Cathedral and town, that together portray one of the best known medieval cityscapes of medieval Europe.

Authenticity

The property has remained continually in use as a place of worship, learning and residence. Durham Cathedral is a thriving religious institution with strong links to its surrounding community. The Castle is accessible through its use as part of the University of Durham, a centre of excellence for learning.

A series of additions, reconstructions, embellishments, as well as restorations from the 11th century onward have not substantially altered the Norman structure of Durham Cathedral. The monastic buildings, grouped together to the south of the Cathedral comprise few pristine elements but together make up a diversified and coherent ensemble of medieval architecture, which 19th century restoration works, carried out substantially in the chapter house and cloister, did not destroy.

The architectural evolution of the Castle has not obscured its Norman layout. Within the Castle, the astral chapel, with its groined vaults, is one of the most precious testimonies to Norman architecture circa 1080 AD. The slightly later Norman Gallery at the east end has retained its Norman decoration of a series of arches decorated with chevrons and zigzags.

The siting of the Castle and Cathedral in relation to the surrounding city has been sustained, as has its setting above the wooded Wear valley, both of which allow an understanding of its medieval form.

Figure 2.14: Immediate Setting of the Durham World Heritage Site

Protection and management requirements

The UK Government protects World Heritage properties in England in two ways. Firstly, individual buildings, monuments, gardens and landscapes are designated under the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 and the 1979 Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act and secondly, through the UK Spatial Planning system under the provisions of the Town and Country Planning Acts.

Government guidance on protecting the Historic Environment and World Heritage is set out in the National Planning Policy Framework and Circular 07/09. Policies to protect, promote, conserve and enhance World Heritage properties, their settings and buffer zones are also found in statutory planning documents. World Heritage status is a key material consideration when planning applications are considered by the Local Authority planning authority. The Durham Local Plan and emerging Local Development Framework will make reference to Durham World Heritage Site.

Both the Castle and Cathedral are protected by designation with the Cathedral Grade 1 listed and also protected through the ecclesiastical protection system, and the Castle Grade 1 listed. The whole property lies within the Durham City Centre Conservation Area, managed by Durham County Council.

This Durham World Heritage Site Management Plan was produced by the property’s key stakeholders. A Coordinating Committee oversees the implementation of the Management Plan by the World Heritage Coordinator. This review of the Management Plan includes boundary revision and setting.

The property lies within a conservation area and care is given to preserving views to and from the property, in particular from the Prebends’ Bridge, where the Castle and Cathedral dominate the steeply wooded island banks forming part of an 18th century designed landscape. Given the topography of the site, and the conservation area surrounding it, the preservation of key views is more important than the definition of a buffer zone. There is nevertheless a need to ensure the protection of the immediate and wider setting of the property in light of the highly significant profile of the Castle, Cathedral and city and its distinctive silhouette visible day and night. This is addressed by examining planning proposals in light of their potential impact on views to, from and of the property, rather than just their proximity to the property itself.

Tourism Management has been an important focus for the landowners and other institutional stakeholders over the last few years, with numerous initiatives being put in place to improve the quality of the tourist offer without compromising any of the property’s values or its ability to function. The property’s collective approach to tourism is one of sustainable development of tourism and providing better and greater intellectual and physical access to the site, as well as delivering a varied programme of world class cultural events that bring larger numbers of people to the property on occasion.

The property faces no serious threats. The main objectives are to continue to maintain the architectural fabric, to ensure integration of the property’s management into the management of the adjoining town and wider landscape, to assess and protect key views into and out of the property and to improve interpretation, understanding and to encourage site-specific research.

2.3 Attributes of the Site, as related to the Statement of Outstanding Universal Value

Figure 2. 15: Durham Cathedral Plan

2.3.1 SIGNIFICANCE 1: The Site’s Exceptional Architecture Demonstrating Architectural Innovation

Key Attributes:

A The architectural design and construction techniques of the nave of Durham Cathedral.

In architectural terms, Durham Cathedral therefore reflects the ambitions of its patrons wishing to outshine the buildings of near contemporaries, to place the cult of St Cuthbert on a par with that of St Peter in Rome, and to incorporate exotic elements from afar in its construction.

Remarkably, for a building that has remained in constant use since its construction, it has survived across the ages as an essentially Norman building – having been spared the extensive remodelling that compromised the historic integrity of many of its contemporaries.

Ever since its completion in 1133, Durham Cathedral has been one of the most important Romanesque Buildings in Europe, and the pre-eminent example of the Anglo–Norman style. It was constructed at the end of a wave of cathedral building in England which

resulted from the reorganisation of the English Church under the Normans. As such, Durham Cathedral was designed to hold its own in the context of a series of new Norman cathedrals in England. It was consciously designed to be the same size as St Peter’s, the mother church in Rome, and in addition to obvious references to that building, indicates an appreciation of architectural trends in other regions of Europe as well. For example, some of its architectural details were probably inspired by architecture in Spain

Figure 2.16: View of the Cathedral, looking North across Palace Green

Figure 2.17 Cathedral Nave vaulting

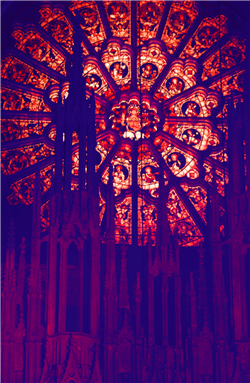

Figure 2.18 Cathedral East Window

Architectural Importance: The real architectural significance of the Cathedral is its role as a milestone in the history of architecture: It is the first successful use of pointed arches on a large scale to support the monumental vault of the nave. The significance of the use of the pointed arch is that it is structurally superior to its precedent, the rounded arch, since it enables greater height to be achieved, while also improving structural stability. In short, the technological success of the pointed arch enabled the emergence of Gothic architecture, which was to have an impact all over Europe in the first instance, and, subsequently, all over the world.

Scale and Aesthetics: The scale of Durham Cathedral is also remarkable, and was made possible by the technological advances mentioned above. The massive scale of construction is offset by the use of the ribbed vaults and pointed arches to create a sense of lightness in the building that belies the sheer weight and volume of stone used in its construction. The rib vaults give the nave a unified appearance and help create a sense of visual movement in the direction of the altar.

Actions:

Enhancing the understanding of the site’s significance

Although the monumentality of Durham Cathedral is appreciated by the hundreds of thousands of visitors that come to the building every year (in the region of 720,000 people), its architectural significance is less well known. Since 2011, the existence of the Durham World Heritage Site Visitor Centre has meant that visitors have been given an introduction to this significance, and it is estimated that perhaps half of the 100,000 visitors that come to the centre per year do learn about the architectural innovations. However, making more out of Durham’s architectural importance would enable an enhanced understanding of the site.

Figure 2. 19 Norman Chapel, Durham Castle

Figure 2.20 Carved Capital of the Stone Columns

B Durham Castle’s Norman Chapel

Durham Castle’s Norman Chapel is an unusually well-preserved example of Norman architecture that provides an important reference for the form, design, and iconography of early Norman religious buildings in England. The carving on the capitals of the chapel’s six columns is a turning point in the evolution of 11th century Romanesque sculpture, and an important reference in the study of English sculpture following the Norman Conquest of 1066.

The Chapel was probably constructed in the late 1070s and described in the 1140s as a “shining chapel, here, supported upon six columns, not too large but quite lovely.” (Prior Laurence of Durham).

The chapel’s state of preservation is remarkable. Its six stone columns topped with carved capitals, herring-bone patterned stone floor, and variegated stone makes it unforgettable despite its small size.

Actions:

Access

The Norman Chapel and Durham Castle are mainly accessible through guided tours, due to the residential nature of the building as part of University College and being a flagship venue for Event Durham. However, there is a general aspiration by heritage related organisations and University College to explore and implement improved access strategies.

2.3.2 SIGNIFICANCE 2: The visual drama of the Cathedral and Castle on the peninsula and the associations with notions of romantic beauty.

Key Attributes:

A The dramatic, dynamic skyline of Durham Cathedral and Castle

The Cathedral and Castle tower over the city, riverbanks, and river, visually uncontested by more recent urban development. Moreover, the juxtaposition of the Castle’s Motte and Keep on one hand, and the Cathedral’s three towers and numerous pinnacles and turrets on the other, and the different visual compositions these form depending on the angle from which they are seen, give the medieval complex a sense of drama and movement.

B The Cathedral and Castle and their immediate setting

i. The romantic setting:

The immediate setting provided by: the undeveloped stretch of river between and including Framwellgate and Elvet Bridges; the steep, forbidding, mature tree lined-river banks, which look like an undesigned woodland landscape; the remaining stretches of the Castle Walls, and the way in which they have been partially covered by the vegetation and eroded by time; Prebends’ Bridge and the view it provides of this ensemble of nature and buildings.

A major programme of woodland and riverbanks management on the Cathedral land has resulted in substantial clearance of over-mature trees and scrub, the renovation of footpaths and the provision of wildlife sanctuaries. However, due to the extent and increasing height of tree cover and the lack of a robust management programme elsewhere along the river banks there is some negative impact on the world-renowned views of the WHS.

ii. The scale of the Cathedral and Castle:

The massiveness of the Cathedral and Castle in comparison to the fragmented nature of the surrounding landscape.

iii. The Pilgrimage Routes to the Cathedral:

The Cathedral’s relationship to its surrounding fabric is unlikely to have changed much since the Middle Ages, due to the Cathedral’s physical dominance with regards other buildings. The Cathedral towers appear and disappear depending on one’s location along one of the limited number of routes leading to the building, and this must have been a significant feature for the large number of pilgrims who would have travelled from afar to get to Durham, and indeed to their modern-day counterparts. Views are reviewed in Chapter 4 and Appendix 1.

Figure 2.21 Peninsula Riverbanks

Actions:

To describe the setting to the WHS and any risks to it. To identify opportunities for integrated landscape management programmes.

C Setting of the World Heritage Site

The inner setting of the World Heritage Site is formed by an ‘inner bowl’ contained by nearby ridges and spurs incised by the meandering River Wear, and a

more diffuse wider setting (‘outer bowl’) contained by more distant high ground including the limestone escarpment to the east and south, and higher spurs and ridges to the west. These form important horizons and skylines in the backdrop of many views of, from and within the WHS, and contain important vantage points from which the WHS is viewed. A review of the setting is covered in Chapter 4 and Appendix 1.

D The visual appeal of the site in its context

i. Form, colour, and materials:

The contrast between the honey-coloured stone of the Cathedral & Castle and Prebends' Bridge; the greenery of the trees and shrubs along the river; and the earthy river banks; and the reflection of all of these in the river.

ii. The patina of history:

The weathered, variegated quality of the Cathedral and Castle stonework.

Actions (for both i and ii):

Ensure that even minor interventions take the aesthetic qualities of the site into account, (interventions such as paving, lighting, outdoor furniture, landscaping, which collectively can have a major impact on the aesthetic quality of the site).

iii. The site by night:

The visual presence of the Cathedral and Castle by night in contrast to the darkness of the river, riverbanks and sky.

Actions (for iii)

To work with WHS partners and the local authority in order that consideration is given to the night-time lighting environment of the WHS when planning new developments adjacent to the site to minimise the risk of light pollution harming the significance of the WHS. To support the use of the 2007 Lighting and Darkness Strategy. 2

Figure 2.22 WHS by night

Figure 2.23: View of the World Heritage Site from the West

Figure 2.24: Palace Green in 1812 (Durham University Library)

iv. The site in changing climatic conditions:

The character of the site changes as weather and season impact on views. This can create striking images highlighting the Castle and Cathedral and how they relate to the river and riverbanks and surrounding townscape.

Particularly memorable, especially from the west, is the effect of sunlight in the afternoon as it brings out the massing of the architecture of both buildings remarkably well, articulating the Castle’s buttresses and battlements, and the details of the Cathedral’s stonework. The sight of Durham Cathedral and Castle in the snow surrounded by the rooftops of Durham, the Castle Walls, the trees, the riverbanks, and the river is remarkably memorable.

v. The routes to Palace Green and the visual unfolding of the site:

The relationship between the Castle, Cathedral and Palace Green on one hand, and the rest of the city on the other, offers a dynamic visual experience to the viewer: the Cathedral and Castle appear in between buildings, and through vistas leading up to the site from the bridges allowing access to the peninsula.

The Cathedral and Castle are practically invisible to passers-by along much of the stretch from Framwellgate Bridge via the city’s marketplace towards Palace Green, and then suddenly appear on Owengate, while the approach from Prebends’ Bridge provides a much more gradual appearance of the Cathedral Tower, followed by the building itself. Elvet and Kingsgate Bridges also offer dramatic, changing views.

The sight of Palace Green itself is a great surprise when seen for the first time, as the narrow winding streets leading up to it give no indication of its massive scale and openness.

Actions:

To work with WHS partners and the local authority in order that development on the routes leading up to the site makes a positive contribution to their impact on the approach to the site.

Figure 2.25: Chapter House, Durham Cathedral

Figure 2.26: Black Staircase, Durham Castle

Figure 2.27: Bishop Hatfield’s Cathedra

Figure 2.28 :Neville Screen, Durham Cathedral

Figure 2.29: Misericord, Tunstall Chapel, Castle

Figure 2.30: Cathedral Organ

Figure 2.31: View of WHS from Durham City

vi. The visual relationship between the Cathedral and Castle and the surrounding landscape.

The sight of monumental historic buildings towering over the landscape and cityscape has inspired visual artists for centuries.

vii. The site’s key views: The world-renowned views of the site to both residents and visitors to the city.

The views of the Castle and Cathedral are world-renowned not just in terms of the city, but in terms of the county as well, with the image of the Cathedral and Castle inextricably linked to people’s image of Durham.

Actions:

Recognise and understand the less obvious key views and those important to residents and people working in or using the city centre.

2.3.3 SIGNIFICANCE 3: The Physical Expression of the Spiritual and Secular Powers of the Medieval Bishops Palatine that the Defended Complex Provides.

Key Attributes:

A. The scale of the spaces and buildings

The massive scale of both the Cathedral and the Castle, and the dwarfing effect they have says much about the status of the Prince Bishops. The Castle is especially dominant when seen from the banks of the peninsula, from Framwellgate Bridge, which historically would have been the main point of access. The Castle was meant to look imposing from that side especially – its scale acting as a deterrent to would-be attackers.

The sense of scale is also conveyed through the experience of Palace Green, where one is surrounded by grand, imposing historic buildings and a huge green space, and can therefore perceive the historic prosperity of Durham; reflecting both wealth and power.

B. The grandeur and richness of the spaces of the WHS

The grandeur of interior spaces such as the Cathedral nave, the Galilee Chapel, the Great Kitchen, the Monks' Dormitory, the Chapter House, Prior's Hall and the Dean's residence, contribute to the physical expression of the secular and spiritual powers of the Medieval Bishops Palatine.

With respect to the Castle, its role as the Bishop's palace since the Norman period is reflected in the scale and decoration of spaces such as the Great Hall, the Black Staircase, the Tunstall Gallery, the Norman Gallery, the Senate Chamber, the Bishop's Suite, and the Senior Common Room.

Some of the spaces of the World Heritage Site combine architectural ‘wealth’ with the notion of cultural wealth, such as John Cosin’s 17th century library, designed as a repository for that particular Bishop’s collection of books, and, in style, emulating the famed library of Cardinal Mazarin in Paris.

C. Architectural symbols of power

There are also actual symbols of power, the most notable being the Cathedra (throne) constructed in the Cathedral by Bishop Hatfield in the 14th century, allegedly intentionally designed to be the highest Cathedra in Christendom.

D. The quality of the workmanship, and the status and reputation of the craftsmen commissioned by the Prince Bishops

The level of architectural patronage and the long history of the Prince Bishops commissioning work from nationally-renowned craftsmen and designers is indicative of the bishops’ role in society at a national level.

Most notable are commissions from Henry Yevele (The Neville Screen, Durham Cathedral, 1380), The Ripon wood carvers (Misericords in the Tunstall Chapel, Durham Castle, originally made for Auckland Castle, early 15th century), Father Bernard Smith (Cathedral Organ, 17th century), and others.

E. The range of buildings reflecting the different powers and responsibilities of the Prince Bishops

The combination of historic religious buildings, grand residential buildings, defensive buildings and structures and administrative buildings, and the fact that they have not been overshadowed by modern construction and development, even to this day, reflects the pre-eminence of the prince-bishopric as the most important position in Durham’s history up until the present day.

Apart from the grand spaces listed earlier, there are a range of more intimate historic spaces. Among these are the Castle’s Norman Chapel, the Deanery’s Chapel of the Holy Cross, and the University Music School, formerly a grammar school.

F. Buildings intended to dominate the landscape

Apart from the visual pre-eminence of the Cathedral and Castle, the fact that they were designed to dominate the landscape is evident through views from them, such as views from the Cathedral towers, and from the Castle's ramparts, Norman Gallery, and keep.

The necessity of the Castle dominating the landscape for defensive purposes is clear. But castles were also symbols of power, and the rebuilding and enlargement of the Castle keep in the fourteenth century was almost certainly a project to reassert the bishop’s authority, probably in the context of an on-going power struggle with the Archbishop of York.

With respect to the Cathedral, scale was of the essence, primarily to reflect the status of St Cuthbert. The construction of the Cathedral to be the same length as St Peter’s, the mother church in Rome, is telling of the ambitions of its patrons, William of St Calais, and Ranulf Flambard, the latter, especially, a key political figure of his time.

Events such as the monks of Durham singing from the top of the Cathedral Tower in commemoration of the Battle of Neville’s Cross (fought in 1346), and on other occasions, emphasize the fact that the Cathedral Towers were not just visual symbols, but were used to reflect the importance of the institution in the social and political life of the city and region.

Figure 2.32: The WHS dominates the silhouette of Durham City

Figure 2.33: LiDAR rendering of City defences (Purcell)

Figure 2.34: Elvet Bridge

Figure 2.35: Framwellgate Bridge

G. The defensive nature of the site

The River Wear was the Castle’s initial line of defence (serving as a moat), and making the Castle walls only the second line of defence (and therefore modest in defensive terms in comparison to the walls of other cities with less substantial natural defences, such as York, for example).

The peninsula, with its steep river banks was well chosen, and the construction of the Cathedral within the Castle precinct would have been especially significant for the community of St. Cuthbert, whose history until the 10th century was one of persecution at the hands of Viking raiders.

Today, the defensive nature of the site is best felt through the experience of walking along the western bank of Durham Peninsula where there is an unmistakable sense of the impenetrability of the medieval complex, and of its complexity and its development over a long period of time.

H. The economic value and significance of some of the bishops' constructions

The two medieval bridges (Framwellgate and Elvet) are reminders of the economic dimension of the medieval bishops’ power. As key points used to control access to the city centre, they would have also been used for the imposition of tolls. Moreover, the fact that Elvet Bridge was lined with shops (of which some still remain) meant that it constituted a commercial street over water, reflecting the fact that the Bishopric was not just a religious, or a political establishment, but an economic one as well.

The 15th century chancery and exchequer building on Palace Green dealt with legal issues related to the Bishops’ property, and managed his revenues. The construction of later court buildings (the latest of which dates from the mid-1800s) is a reminder of the Bishops’ economic might over the centuries.

The Bishop’s Mint, although today remaining only in the name of ‘Moneyer’s Garth’ a 19th century building constructed on the site of the mint on Palace Green, was another of the Bishop’s income- generating institutions, and stayed in operation until it was shut down by Henry VIII.

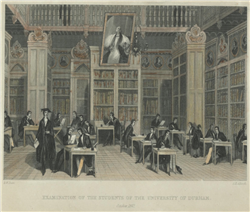

I. The site's intellectual importance across the ages

The Cathedral Library and Bishop John Cosin’s Library (now part of Durham University’s Palace Green Library) are physical manifestations of the intellectual importance of Durham.

Durham’s importance as a place of learning dates back to at least the 11th century with the founding of the Benedictine Monastery by Bishop William of St. Calais. Durham’s links with other educational

establishments were strong from an early age, both to other religious establishments, as well as to centres of learning, like Oxford University, where the Durham monks founded Durham Hall in 1291, expanded into Durham College in the 14th century by Bishop Hatfield and now Trinity College.

The Cathedral and Palace Green Libraries convey a sense of the intellectual wealth of Durham, and its historic pedigree.

Actions:

Issues of transport and access - getting people to the Cathedral on Sundays and after evensong (times when the Cathedral Bus Service is not in operation), making it hard for older members of the congregation and for Cathedral volunteers to access the building. Access through the north and south porches restricts visitors, processions and banners.

Figure 2.36: Monyer’s Garth

Figure 2.37: Monks Dormitory, housing the Cathedral’s Library

Figure 2.38: St. Cuthbert’s Shrine

Figure 2.39: Bede’s Tomb

Figure 2.40: Cosin’s Library, 1842, examinations (Gilesgate Archive)

Figure 2.41: Cosin’s Library today

Figure 2.42: Student accommodation in Castle

Figure 2.43: Student accommodation on Owengate

2.3.4 SIGNIFICANCE 4: The Relics and Material Culture of the Three Saints, (Cuthbert, Bede, and Oswald) Buried at the Site

Key Attributes:

A. St Cuthbert's Shrine & Relics

The sanctity of St Cuthbert's Shrine is emphasised by the combination of: its elevated position above the floor level of the Chapel of the Nine Altars and the side aisles; the historic building fabric and objects (the Frosterley marble gravestone, the Neville Screen, and the statue of Cuthbert holding Oswald's head); as well as by the modern furnishings of the well-maintained shrine such as the canopy, banners, cushions, pew, and the candlesticks, together emphasising the continued importance of St Cuthbert. The recent donation of the St Cuthbert Banner, based on the medieval design, continues this tradition of honouring the saint.

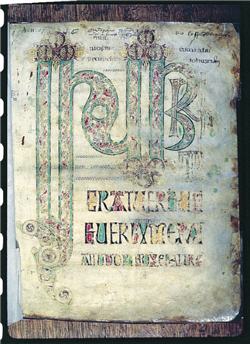

The continued existence of many of St Cuthbert's relics in Durham Cathedral (his coffin, pectoral cross, textiles, the Durham Gospels, and other early religious texts belonging to the community of St Cuthbert) is notable. The sense of ownership of St Cuthbert by local people is a remarkable and significant element of the Cathedral’s life.

Actions:

Improving access for disabled people to the shrine (which was built to impress rather than be accessible).

B. The Tomb of the Venerable Bede

The importance afforded to Bede's tomb is emphasised through the combination of the Frosterley marble cenotaph, the epigraphic sculpture about Christ the Rising Star, the candelabra, and the pew with its cushion produced by the Cathedral broderers, and the careful creation of an implicit curtilage area around the cenotaph itself.

2.3.5 SIGNIFICANCE 5 The Continuity of Use and Ownership over the Past 1000 Years as a Place of Religious Worship, Learning and Residence

Key Attributes:

A. The continued function of the Cathedral and Norman Chapel as religious establishments.

The Cathedral's role as the seat of the Bishop and centre of the Diocese of Durham, and as one of the most important centres for Christian worship in Britain, through dedicated regular congregations, and civic and diocesan services. Its role is primarily that of 'a house of prayer, ' offering a place for people from all backgrounds to come together in worship with a common purpose and for more personal, quiet prayer. Durham Castle’s Norman Chapel also continues in use as a place of worship to the present day.

B. The use of the buildings (old and new) of the World Heritage Site by Durham University and Durham Cathedral for the purposes of learning, scholarship and education.

These uses are extensive, and integral to the life of the site. They include the use of the Castle as a Durham University college (officially called University College, Durham); the use of Cosin's Library and its annexes as a university library; the use of Cosin's grammar school as an academic department (music); the use of part of Cosin's almshouse/educational complex as a lecture room/ study space; the use of Divinity House as the Department of Theology; all other uses of the buildings that may not specifically be related to their original function but ensure that they remain viable.

Also children have been educated on the site for at least 600 years, currently expressed in the existence of the Cathedral Chorister School, and the continued tradition of musical education and performance. There are also the Cathedral and University Education departments, both located on the site, and responsible for educational outreach to both children and adults.

Actions:

- Support the educational uses of the site and promote their continuation when new development is considered elsewhere in Durham.

- Ensure that the emphasis on English Church music within the University remains strong, to ensure that, in turn, the musical link between the University and the Cathedral is not weakened. The University Music Department currently attracts a sizeable number of students with an interest and background in the English choral tradition, and these contribute to the musical life of the Cathedral, through choirs and concerts.

- Vehicular access to the Chorister School continues to cause traffic problems on the Bailey. A walking ‘school bus’ is provided, but the drop-off point needs new arrangements to allow parents to drop off and collect their school children without running the risk of incurring parking fines.

- Delivery vehicles bringing food and essential supplies to the Colleges, school and restaurants contribute to congestion, off-site repackaging into smaller vehicles would make a significant difference.

C. The use of the buildings of the World Heritage Site for residential purposes

The use of the Castle (The keep, the rooms along the Norman Gallery, and in the kitchen block) for student accommodation.

The use of buildings on Owengate and North Bailey for student accommodation (currently by Hatfield and University Colleges).

The continued use of the houses within the Cathedral College for residential purposes and the fact that most of the residents are associated with/employed by the Cathedral.

Actions:

- Ensure that the immeasurable value that this is a residential site is not compromised.

- Noise at night from students returning to the hill colleges is a problem for residents and other students and needs to be addressed.

- Access for residents at busy times and when there are major events needs to be maintained at all times. Any temporary arrangements must be negotiated and notified well in advance to allow dissemination of the information.

Figure 2.44: Residences in the Cathedral College

D. The use of the buildings of the site for administrative purposes

The existence of the Cathedral Office on the site, running the Cathedral's affairs from the site, as has been the case at least since the late eleventh century.

Actions:

Address shortage of office space as the Cathedral’s staff increases.

E. The continued existence of building-related trades and crafts on the site

Craftsmen with traditional skills such as stonemasonry are still employed by and on the site on a permanent basis and are integral to the maintenance and preservation of the historic building fabric. The Cathedral and University each have a stonemasons' yard, and building traditions are passed on from one generation to the next through the traditional system of apprenticeship.

Actions:

Actively encourage the site to continue to provide opportunities for building-related trades and crafts, and for apprenticeships, which ensure that craft traditions do not die out. Make the delivery of these crafts more visible to the visiting public, to enhance their understanding of the processes of historic fabric maintenance. Seek sources of funding to help make this possible.

F. The records documenting the use of the site across the ages

Extensive documentary evidence in the Cathedral and University archives chronicles the use of the site, works undertaken, people associated with it, activities and events.

Figure 2.46: Cathedral Stonemason at work

2.3.6 SIGNIFICANCE 6: The Site’s Role as a Political Statement of Norman Power Imposed upon a Subjugate Nation, as one of the Country's Most Powerful Symbols of the Norman Conquest of Britain

Key Attributes:

The Cathedral and Castle as a monumental ensemble whose original functions are immediately recognisable, even from a distance.

The view of the massive ensemble of the Cathedral and Castle, especially from the west, and the way in which they tower over the city, river and landscape is an uncontested symbol of power, and attests to the site’s historic role in defence against Scottish invasions.

Actions:

The statement of power, although clearly recognised by local historians and interested groups, is less well understood by the general visitor and would benefit from more interpretation to share this with wider audiences.

2.3.7 SIGNIFICANCE 7: The Importance of the Site’s Archaeological Remains, which are directly related to its History and Continuity of Use over the past 1000 years.

Key Attributes:

The continuum of significant archaeological/historical information offered by the site

The wealth of archaeological remains, documents, collections, and building archaeology that the site offers, and the unbroken link between the site's extant buildings, its archaeological remains, and its moveable heritage. Durham is especially fortunate to have extensive archival material which contributes greatly to shedding light on the social, political, religious, cultural and economic context that shaped its buildings.

The existence of Durham University’s Archaeology Department and the fact that Durham Cathedral has a resident archaeologist on its staff (only one of two cathedrals in the country to do so) also means that on-site archaeological work, research and analysis is on-going.

Actions:

- Ensure that this wealth of archaeological work, research and analysis is made widely accessible through publication.

- Review and develop options for shared archaeological storage and conservation facilities for the Cathedral, University and County Council.

Figure 2.47 : Archaeological Excavation, the Great Kitchen, Durham Cathedral (J.Attle)

2.3.8 SIGNIFICANCE 8: The Cultural and Religious Traditions and Historical Memories Associated with the Relics of St Cuthbert and the Venerable Bede, and with the Continuity of Use and Ownership over the Past Millennium.

Key Attributes:

A. The continued veneration of Cuthbert and Bede

The continuity of local, site-specific traditions developed over time by the Cathedral community and clergy, by the University, and by community groups such as miners' lodges, school groups and others. Cathedral services related to St Cuthbert and the Venerable Bede; Durham University college services also linked to the two saints (Such as Hild Bede Day); Cathedral services specific to Durham and its history such as 'Founders and Benefactors' and St Cuthbert's feast day all exemplify the continued importance of the two saints in the cultural, social, and religious identity of Durham.

B. The site's importance as cornerstone of community identity and as a rite of passage

Use of the Cathedral for school and college carol services and events, Miner's Gala service, Durham University matriculation and graduation ceremonies, weddings, among others.

The use of Durham Castle for important University and civic functions, such as congregation processions, ceremonies related to the judiciary, University College events, and for weddings.

The continued importance of the processional route into the Cathedral, manifested in celebrations such as the Miner's Gala procession, the Palm Sunday St Nicholas and New Year’s Eve processions, and University Matriculation and Congregation ceremonies.

The presence of community memorials such as the DLI Chapel and miners’ memorials.

C. The site's multi-functionalism and adaptability of use

The primary use of the buildings of the World Heritage Site for a multitude of non-tourist-related functions, and their ability to continue to serve their community while remaining important visitor attractions says much about their versatility.

Actions:

Space remains highly sought after (and limited) on the World Heritage Site – especially for meetings and storage. Sharing spaces (such as archaeological storage space) appears to be an appropriate strategy for mitigating the shortage of space.

D. The continuity of ownership

The ownership of the site by institutions that evolved from the original community of St Cuthbert, such as the Chapter of Durham Cathedral and, in turn, Durham University and its independent colleges, demonstrate an evolving, yet unbroken chain of ownership over the course of a millennium. This is further reinforced by the continuation of the original use of some of the buildings on the site.

1 These lateral supports have turned out not be flying buttresses, and the date of the construction of the building is 1093-1133, not 1137-39 as stated above.

2 City of Durham, Lighting and Darkness Strategy, Spiers and Major 2007