If a place is a World Heritage Site, it means that it has been inscribed by UNESCO (the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation) on its World Heritage List. To qualify, a site must be of outstanding universal cultural or natural value (or both). A site does not necessarily have to be old to be considered worthy. Sydney Opera House, inaugurated in 1973, and the City of Brasilia, designed in the 1950s, are two examples of modern World Heritage Sites.

There are currently 1154 sites on the World Heritage List, in 167 countries. Of these, 897 are cultural, 218 are natural, and 39 are mixed sites. New sites are added to the List every year.

Left: The National Theatre, one of the civic buildings of Brasilia; and, Right: Sydney Opera House, two modern World Heritage Sites.

© (L)UNESCO (Our Place); (R) F. Bandarin

The Process of Inscription

Before a site can be given World Heritage Site status, it must first be put on a tentative list of prospective World Heritage Sites by the government of the country in which it lies. Every year, each country has the right to put forward one site from its tentative list for consideration for inscription onto the World Heritage List. This requires extensive preparatory work, as the inscription process means that a site has to demonstrate how it meets one or more of UNESCO’s ten criteria for eligibility. If a site is successful, it means that it is recognised as being of outstanding value to humanity as a whole.

Monitoring and Managing a Site

Sites on the World Heritage List are monitored by UNESCO to ensure that whatever makes them outstanding is preserved. Outstanding value can be tangible or intangible — for example, Durham Cathedral’s significance as a great historic building is a tangible aspect of its outstanding value, while the fact that the shrine of Saint Cuthbert has been a place of pilgrimage for over 1000 years is an intangible aspect. It is the responsibility of the country in which a site lies to ensure that it is properly preserved.

Heritage at Risk

If a site is under threat, for example through neglect, wilful destruction, or natural disasters, to name a few, it can be put on the World Heritage in Danger List. This draws the attention of the international community, and also makes a site eligible for financial support from the World Heritage Fund. In severe circumstances, UNESCO can revoke a site’s World Heritage status if it feels that its integrity has been compromised to the extent that it has lost the qualities that made it outstanding.

For example, the Arabian Oryx Sanctuary in Oman, inscribed in 1994, was delisted in 2007 because of the Omani government's decision to reduce the size of the sanctuary by 90%.

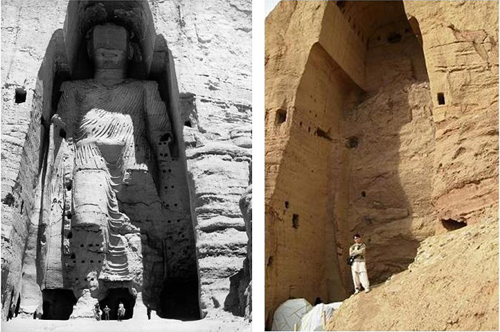

Two views of one of the Buddhas of Bamiyan in Afghanistan. The image to the left was taken in 1963. The image to the right was taken after the wilful destruction of the Buddhas by the Taliban in 2001. As a result, the cultural landscape and archaeological remains of the Bamiyan Valley were listed and immediately put on the Heritage in Danger List in 2003.

The List and New Site Categories

In 1994, UNESCO decided that the World Heritage List needed to be balanced, representative, and credible, meaning that it would need to better reflect the diversity of outstanding cultural and natural value across the world in its broadest possible sense. Until then, European sites, historic towns, religious sites and ‘elitist’ (as opposed to vernacular) buildings were over-represented on the list, while there were very few examples of living cultures, especially traditional cultures, and major gaps in the representation of natural areas such as savannas, lakes, and tundra and polar systems.

Today, new categories of sites are actively being encouraged. These include cultural landscapes, itineraries, industrial heritage, deserts, coastal and marine sites, and small island states.

Aerial view of La Chaux-de-Fonds and Le Locle, two adjacent watch-making towns in Switzerland, inscribed on the World Heritage List in 2009, because of their value as an urban ensemble entirely dedicated to a single industry. They have been constructed by and for watchmaking, for which Switzerland is world-renowned. They are a good example of the broad way in which UNESCO now defines 'Outstanding Universal Value.'

© UNESCO