The building of monumental cathedrals in the middle ages was a reflection of faith and the channel for much of the creative energy of medieval European society.

Although cathedral building was driven by religious figures or institutions, it was often a community effort. From the mid-twelfth century, the Church started granting indulgences (forgiveness of sins) to those who would help to build a church or cathedral, and therefore, rather than going on crusades, which had been a popular means of absolving sins in the late eleventh century, people dedicated more effort to the construction of houses of God instead.

There was always a faction among the pious that disapproved of excessive spending on the construction and decoration of lavish religious buildings, but these were a minority, and the dominant feeling was one of great enthusiasm, ambition, and a desire to excel in this quest to construct magnificent buildings reflecting God's glory.

As cathedrals took decades, and often even centuries to complete, few people who worked on them expected to see them finished during their lifetimes. Being involved in the construction of a cathedral, even as the building patron, required a willingness to be part of a process that was larger than oneself.

Relics of important saints were an important source of prestige but also of income. For the community of St Cuthbert, the most important relic was, of course, the incorrupt body of the saint himself, which was preserved in this wooden coffin dating from the 7th century. The coffin is still on display inside Durham Cathedral.

© Durham Cathedral and Jarrold Printing

Leading & Financing the Construction

The construction of a cathedral was often led and financed to a large extent by the Cathedral Chapter (the senior clergy), while bishops tended to contribute at their own free will. However, at Durham, the bishops' contribution - both intellectual and financial, was substantial.

Cathedral chapters financed the construction by actively raising money from their congregations, by creating systems of fining clerics for transgressions such as tardiness, and by arranging for relics to go on tour. Taking relics on tour was a very lucrative means of fund-raising.

Given their importance and longevity, building projects usually received at least some sort of input from the head of the religious establishment concerned. This is true even today. Seen here, the Bishop of St Anthony's Monastery in Egypt discusses the construction of a new building on-site with his architects and two senior monks.

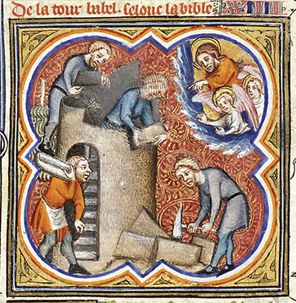

Building in medieval times was as complex a process as it is today, involving an 'assembly line' of craftsmen. This image from a fourteenth-century French manuscript, (Folio 19 of Giuard des Moulin's Grande Bible Historial) illustrates that well.

Labourers & Builders

The workforce involved in the construction of a cathedral varied considerably in terms of skill. At the lower end of the scale were labourers who would do basic jobs such as transporting building materials, digging for the foundations, or removing earth. Contrary to the common belief that much of this was voluntary labour, substantial records exist to prove that most labourers were paid.

Higher-skilled workers linked to a construction site included quarrymen, plasterers, mortar-makers, stone-cutters, and masons. Practical considerations determined the work process. For example, as transport was very costly, stones were often dressed (shaped) in the quarry. Athough stone cutting could take place all year, masons, the ones responsible for actually laying the stone, could not work in winter, as frost would prevent the mortar from binding the stones.

Stone Cutters and their Work

Stone cutters often lived itinerant lifestyles, moving from one construction site to another. They would either be paid by day, or by piece. Piecework was often reserved for new craftsmen or those recruited for short periods. Such craftsmen carved their mark on every stone they cut, to enable them to calculate how much they were owed. With time, maker's marks became a sign of pride and grew more elaborate. Maker's marks can still be seen on some of the stones in Durham Cathedral.

In early Romanesque buildings, such as Durham Cathedral, frescoes were most common means of interior decoration, and stone carving was restrained. However as stone cutters' skills developed, sculpture evolved into an essential component of the design of later buildings. Stone sculptors became more and more independent, seeing themselves as artists rather than skilled craftsmen.

In parallel, as architectural technology developed further, greater expanses of glass became possible. This led to stained glass becoming an important decorative medium in religious buildings, replacing frescoes as the means to depict religious scenes.

Much of the information on this page comes from The Cathedral Builders by Jean Gimpel, (PIMLICO: London, 1993).

Excavations in the Monk's Dormitory at Durham Cathedral revealed some stones that had not been exposed since they were first put in place in the 11th or 12th century. The original tooled finish of the stone can be seen above, as can a maker's mark in the centre of the photograph.

© Jeffrey Veitch