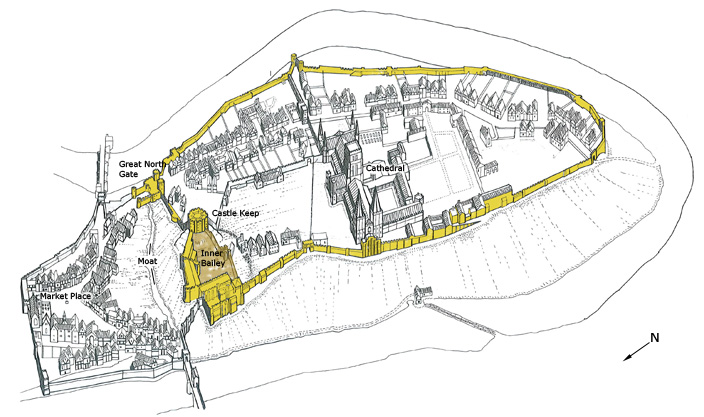

The Castle walls comprised much of the Durham Peninsula, including the Cathedral Precinct.

View of Durham Peninsula showing the Castle boundaries. Few visitors realise how extensive these boundaries were; it is often wrongly assumed that the Castle consists simply of the keep and the inner bailey (shaded in brown).

© Durham County Council (Based on a drawing by John Lines, 1980).

Building the Outer Walls

Though nature had made the city a fortress, he made it stronger and more imposing with a wall....."

A monk of Durham, writing about the 11th century Bishop Flambard. (Anglia Sacra, i, 708).

Masonry walls were built around the peninsula between 1099 and 1128 by Bishop Flambard. These were probably a rebuilding of earlier Anglo-Saxon defences.

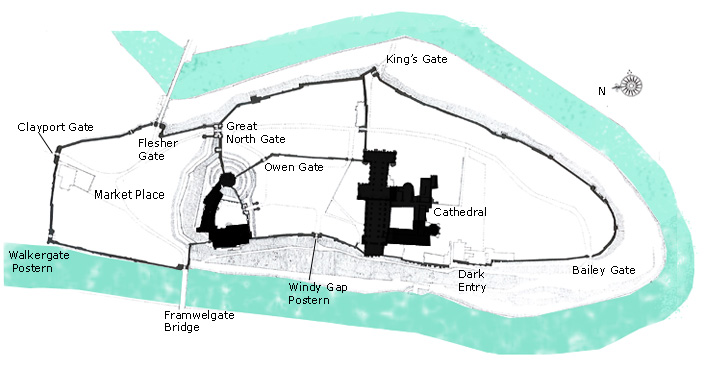

In addition to a wall around the southern part of the peninsula, there was a wall around Palace Green and another around the marketplace.

The walls, strengthened with flanking towers and buttress turrets, followed the contours of the hill rising up from the river banks on all sides except the north, where a wall of great strength, varying from 10m to 15m in height, was built to the north of the castle with a dry moat outside this (along modern Moatside Lane).

There was a massive gate in this northern wall, the North Gate, at the southern end of what is now Saddler Street.

Two other gates were present in the walls, leading to fords across the river: Kings Gate (on modern Bow Lane) and Water Gate or Bailey Gate (at the southern end of South Bailey).

There was also a postern (secondary gate) Dark Entry’ in the Priory, while medieval references to a ‘Windishole Gate’ suggest another such gate at the modern Windy Gap.

The fortified peninsula had numerous gates, all of which have disappeared. Only their names survive as reminders of where they would have been.

Artist's rendering of Kingsgate, as it may have looked.

Kingsgate was a late Norman structure that led to a ford in the river. Later, a bridge known as Bow Bridge was constructed over the ford. It was located just north of the modern bridge seen in the image below this one.

The name Kingsgate comes from a story about William the Conqueror's visit to Durham in 1072. According to the legend, William doubted the fact that St Cuthbert's body had not decomposed, and ordered his coffin to be opened. Before this could be done, the king was struck by a fever, and afraid that he had offended the saint, fled Durham from this point, never to return.

© City of Durham Council

The current Kingsgate Bridge, built in the 1960s by Ove Arup very close to the site of a late Norman Bridge.

The Outer Bailey Walls Today

Although much overgrown, the peninsula’s outer fortifications can still be seen along the river banks. These are in fact the walls of the castle, not of the city.

View of the Castle walls at the top of the river banks. After the river itself, these would have formed a second line of defence. Evidently, the fortifications were effective: Durham Castle was never captured.